|

|  |

Choose an article below: Choose an article below:

An Extinct Species May Walk Broadway Again

By JESSE McKINLEY

Published: June 26, 2005

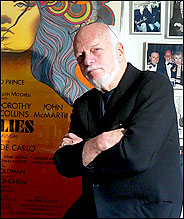

ONCE upon a time, there was a mythical creature that lived along Broadway. Armed with a Rolodex and a nice office, he had access to all the weapons of the trade, including talent, money and good taste. He was called a "creative producer," and according to Harold Prince, who produced a couple of shows with titles like "West Side Story," "Fiddler on the Roof," and "Cabaret," he is almost extinct. ONCE upon a time, there was a mythical creature that lived along Broadway. Armed with a Rolodex and a nice office, he had access to all the weapons of the trade, including talent, money and good taste. He was called a "creative producer," and according to Harold Prince, who produced a couple of shows with titles like "West Side Story," "Fiddler on the Roof," and "Cabaret," he is almost extinct.

"All of the shows I produced started in this office," said Mr. Prince, known as Hal, 77, speaking from his perch at Rockefeller Center. "You come up with an idea, you get the book or play or script, and you get the right author for it. Then, you get the right composer, the right lyricist. And then, you put it all together."

He continued: "And that, I think, is rarer today. I think people come to producers and say, 'We have this thing, here it is, want it?' And then they'll do a reading - and let's do a workshop and whatever. Which is fine, but it isn't the way I did it."

Mr. Prince has a point. Consider the three major new commercial musicals of the 2004-5 season.

"Monty Python's Spamalot" was the brainchild of Eric Idle, an original Pythonite who took the idea to the producer Bill Haber. The composer David Yazbek and the book writer Jeffrey Lane, meanwhile, thought the movie "Dirty Rotten Scoundrels" would make a good musical, and started working with the producers Marty Bell and David Brown after they had already approached MGM about getting the rights.

And "The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee" was originally written as a play, and was converted into a musical only after the playwright Wendy Wasserstein saw the show and recommended it to the composer William Finn. Mr. Finn, who wrote the songs and lyrics, then called David Stone, a producer ("Wicked"), about coming on board.

In each case, the producers were involved early on but didn't instigate the making of the shows, though each had ample creative input, once the ball was rolling.

That is why Mr. Prince has now teamed with Columbia University to establish a fellowship program devoted to developing those "creative producers." The program, named in honor of the Broadway producer T. Edward Hambleton, who was a founder of the Phoenix Theater, will give student producers the chance to develop shows from scratch, culminating in a presentation before potential investors.

Mr. Prince may be right that the species of creative commercial producers has been dwindling for some time now, yet is he also right in thinking that his method is the best way to create a new musical? Or is he nostalgic for a Broadway that doesn't exist anymore, one that didn't require $10 million or more to mount a musical? Have the days of the great producer gone the way of the old movie studio system? Perhaps there's some benefit to the fact that artists now have more power than they used to?

Kevin McCollum, whose producing credits include "Rent" and "Avenue Q," says he absolutely views himself as a creative force - "I'm not a manufacturer; I'm in the research and development business" - but he acknowledges that the principal artistic voice remains the writer's.

"Every project has a motor, and we always feel the motor should come from an artistic sensibility, and that usually comes from an author," Mr. McCollum said. "And then we try to put a team together that has a similar philosophy to get a show produced."

Mr. Prince, of course, knows a thing or two about close collaboration with writers, having worked with Stephen Sondheim repeatedly on shows like "Company," "Follies" and "Pacific Overtures," which were all directed and produced by Mr. Prince.

But today's producers are also undoubtedly dealing with a much more complicated business than the one Mr. Prince was when he produced his first show, "The Pajama Game," in 1954, using borrowed pajamas, borrowed fabric and a raft of borrowed sewing machines.

"The skill set that a producer needs in the current Broadway environment has changed dramatically over the decades," said Jed Bernstein, the president of the League of American Theaters and Producers, citing a number of new considerations, including "the dramatic rise in financial and development importance of the road, the increase in the number and complexity of marketing channels, and the sheer number of people involved on both the management and creative side."

It is true, as Mr. Prince says, that all too often Broadway's current "producers" are actually just moneymen: deep-pocketed corporations or "conglomerations of very wealthy people" looking to be "one of 15 names over the title." Neither group is exactly known for its bold, artistic risk-taking, he says.

"So many of the shows that I was able to do would never have been done under the current system," Mr. Prince said. "Because we weren't taking the pulse of the audience, and we weren't checking box-office demographics. We were doing 'West Side Story.' And what I'm saying is that I sadly believe a good deal of art is lost because of this switch."

But with the ever-rising costs, few producers have enough money to single-handedly produce a show and thus must find multiple partners to spread the risk. "Dirty Rotten Scoundrels," for example, which cost more than $10 million, has 20 above-the-title producers, while "Spamalot" ($12 million) has 13. Many shows now guarantee a producer credit - regardless of whether you know the difference between stage right and the stage manager - as long as you give a set amount of money to the production. That many cooks make for a very crowded creative kitchen, and sometimes leave experienced producers acting as little more than glorified general managers for unwieldy groups of Broadway naifs. Marketing meetings at Broadway advertising companies like Serino/Coyne, for example, sometimes burst out the doors of the conference rooms, with assistants sitting in the hallway, and cheese Danishes spread thin.

Some producers on Broadway, of course, are still front and center in developing new work. Margo Lion, for example, worked for four years on "Hairspray," optioning the movie and stewarding the musical version through numerous readings. Judy Cramer built the blockbuster "Mamma Mia!" from the ground up, and Cameron Mackintosh is also known for being extremely hands-on. Marc Platt, a producer, and Mr. Stone also worked closely with creators to develop "Wicked," as did Mr. McCollum and his partner, Jeffrey Seller, to develop "Rent," and "Avenue Q," which both started in the nonprofit sector.

Indeed, nonprofits are one of the most consistent producers of new musicals, perhaps most famously evidenced by "A Chorus Line," which came out of the Public Theater and eventually ran nearly 15 years on Broadway. Nowadays, a common arrangement is having commercial producers act as financial supporters - providing so-called enhancement money - who pick up a show and take it to Broadway, only after, and if, good reviews come in.

Mr. Prince, in fact, was one of the first producers to do that, taking a 1974 production of "Candide" to Broadway from the Chelsea Theater Center of Brooklyn. (That show, ironically, was one of the last that Mr. Prince produced before leaving producing - unhappy at the state of things - to pursue directing.) But he feels that costs have risen so much that it is unfair to ask nonprofits to bear that risk anymore. "I don't think you can ask them to take that responsibility," he said.

And while corporations are sometimes derided as the great evil of Broadway, they are often the most likely to use the traditional model that Mr. Prince endorses. For example, when Disney decided to turn its 1999 hit animated movie, "Tarzan," into a musical, it followed almost the exact method Mr. Prince describes (and the one the company used with its blockbuster "The Lion King"): getting an idea, hiring a creative team and closely monitoring its progress. "Tarzan," with music by Phil Collins and design and direction by Bob Crowley, has been fast-tracked and is due on Broadway next year.

Students of the Hambleton fellowship - the T. Fellowship, officially, as in T. Edward Hambleton - will have to learn the current ways of producing as part of their studies, Mr. Prince said. But it is clear that his heart lies with the method that he learned, and one that proved to be successful for him (and for his investors; last week Mr. Prince sent out yet another round of checks to his original backers of "Fiddler," "Cabaret," and "West Side Story").In addition to lecturing to students, Mr. Prince said he would also be taking lunch with the Hambleton fellows.

It is an act, he said, of self-interest as a director - "I would like nothing better than to work for one of these people," he said - and of self-preservation for producers everywhere.

"If the idea started with you, if you found the book, optioned the play and got the idea for the musical," he said, "you're not going anywhere."

|

| |